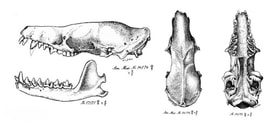

First, I have some exciting news from the Caribbean! Spanish versionHave you heard the recent news about Desecheo island? This island located northwest of Puerto Rico has been declared free of invasive mammalian species! The results are a fantastic win for island conservation after almost half a century of working towards the eradication of rats and goats. Rats are the main predators of bird nests and are an extremely difficult species to manage and remove from an island once it has invaded. On the other hand, goats destroy the native vegetation thereby destroying habitats for other species. Eradicating these two invasive species is key for the restoration an island ecosystem such as Desecheo. This restoration project was a collaborative effort by the Federal Fisheries and Wildlife Service, Island Conservation, the Federal Department of Agriculture, Bell Laboratories and Tomcat. Cheers to the team, and congrats! …For more info: Biologists have confirmed invasive predators absent from Desecheo.   Small Indian mongoose introduced to several islands in the Caribbean and Pacific Small Indian mongoose introduced to several islands in the Caribbean and Pacific Now that we are on the topic of invasive species… as you may (or may not know) one key protagonist in my research is the small Indian mongoose (Herpestes auropunctatus). This species is listed as one of the worst invasive mammalian species, was introduced to many islands in the Pacific and in the Caribbean, and blamed for the decimation of many birds, reptiles and amphibian species. Not too long ago a paper by Dr. Francisco Watlington Linares, a geography professor at the University of Puerto Rico, landed in my email inbox. His article titled, “Apparent suspects: Rats and mongooses ¿ecological plagues? “, has been in the back of my mind for a while . Dr. Watlington argues that mongoose and rats in Puerto Rico came to occupy a niche (a place in an ecosystem) left empty when colonizers drove to extinction mammalian species living in the island. This argument immediately caught my attention for various reasons, one of them being that at the time (2014) I was just getting involved with the concept of “Novel Ecosystems” through my traineeship program. I truly believe this is an interesting hypothesis to be explored (at least for the mongoose), however the evidence presented by Dr. Watlington to support his argument did not really convince me that mongooses where occupying a niche left by an extinct species. In the following paragraphs I try to explain why I was not convinced. I agree with Dr. Watlington in that we should carefully study the role of both mongooses and rats in the faunal assemblages of island ecosystems and I appreciate his willingness to challenge accepted knowledge, but I have many concerns with the evidence and conclusions that he has presented. His main argument is that mongooses are filling an ecological functional gap in the food web of the island. He proposes that the extinct Puerto Rican shrew (Nesophontes edithae) is analogous to the mongoose, and although he is not explicit about this, he may be proposing that the faunal community in Puerto Rico would have been unaffected by mongoose introductions on the island. Left column. Top : Nesophontes island shrew, it is said that the larger species were the size of a mole (Scalopues aquaticus) or a chipmunk (Tamias stiatus). Middle: A 750-year-old Nesophontes skull found in an owl pellet. Bottom: A drawing of skull remains. Right column. Top: Small Indian mongoose, it about the size of an adult ferret (Mustela putorius furo). Bottom: The cranium of Herpestes ichneumon (another species of mongoose) The idea of niche replacement by mongoose has an ecological and evolutionary timing mismatch. First, Nesophontes is classified as an insectivore which went extinct shortly after European arrival (i.e. 16th century)(Turvey, 2010). Mongooses are omnivorous in the order Carnivora, a totally different guild that those mammals classified in Insectivora. This begs the question, was the faunal community in the island affected by the absence of the shrew in the next 400 years before the mongoose was introduced? The role of Nesophontes in the food web remains largely unknown. On the other hand Dr. Watlington states “their [Nesophontes] cranium and mandibules, are parallel to the mongoose”. This is incorrect. Mongoose cranium and mandibles, especially the canines, are vastly different from the Puerto Rican shrew. Differences start with the craniums: elongated snout of a shrew and the viverrid resemblance of the mongoose. On a study by Turvey(2010), they further found that the upper canines of the shrew possess distinctive, well defined longitudinal grooves which closely resemble other species with known dental venom delivery systems, whereas the mongoose simply does not. Given the reasons Dr. Watlington provides for seeing the mongoose as a replacement of a functional analog, his hypothesis is highly misleading. Naturalized species: "an introduced species that has adapted to and reproduces successfully in its new environment. A concept by which, after some time or generations, immigrants or their descendants are considered to be native."My general take on this: I believe the author undermines the evidence from multiple mongoose studies about their ability to negatively affect other species. He states that in 1992, one herpetologist (Robert Henderson) made the case that the real causes of herpetofaunal decline in the islands was due to biogeographical factors and habitat loss, which is certainly true, but we need to factor in that species introductions also work synergistically with habitat loss and biogeography. Giving more weight to one in order to negate the other, and doubting the large amount of research about mongoose predation on islands, is not advancing our understanding and implications for conservation management. It is known that mongooses are not the sole cause of species declines, but they are an important predator for many species along with other mammalian predators (feral cats and rats), disease or habitat loss. In the end, we know that the management of mongoose - or other exotic predator (feral cats and dogs, birds, and rats) - by wildlife managers will continue as long as endangered and vulnerable species are still threatened and the destruction of habitat remains rampant. Dr. Waltington presents an interesting hypothesis, however, we are lacking strong paleontological and ecological evidence that can reveal the exact mechanisms by which several vertebrate species had gone extinct in Caribbean islands throughout our lifetime and the role of mongooses in shaping faunal communities. I understand that Dr. Watlington wants to get a point across that species are able to adapt and that the mongoose’s effects on endangered species sometimes are exaggerated; however, he did not provide strong evidence to prove otherwise or provided a justified reason for ecologists to stop managing for a damaging species. We are experiencing accelerated rates of climate, land-use change and species invasions which result in rapidly changing ecosystems and consequently a shift in species distributions and novel assemblages. Thus, the native vs exotic dichotomy becomes an obsolete approach for managing species. Rather we need to look at how to efficiently manage species, their habitats and evolve as stewards of ecosystems. Recently, the term “novel ecosystems” was coined to challenge our way of thinking about interventions in ecosystems. It is not my intent to discuss the literature on novel ecosystems (also termed: no-analog, emerging, recombinant) in this blog, but to hint at ways in which this approach can be helpful for managing landscapes in the face of rapid change. The concept of novel ecosystems has emerged from the field of restoration ecology, which is dominated by plant biologists, but little work has been done on faunal communities. From a faunal perspective, novel ecosystems can contain non-native vegetation or animals, have native species mixes not previously found, have altered abundance or interactions, no longer contain historical ecological keystone species or engineers, or have missing or added trophic levels (Kennedy, Lach, Lugo, & Hobbs, 2013; Lugo, Carlo, & Wunderle, 2012). The novel ecosystem concept does not advocate for giving up on invasive species control where needed or that no-analog species mixing is always a good thing. It does call for a new and realistic management approach consistent with the results of humans shifting species and the novelty that results from this. Puerto Rico, similar to other islands in the Caribbean, has its current faunal diversity due to the large number of introduced species that have become naturalized (Lugo, Carlo, & Wunderle, 2012). Without underestimating the potential negative effects mongooses on islands, it is conceivable that mongooses occupying these tropical systems are key members of the faunal assemblages. Therefore evaluating consequences of intense species control cannot be ignored. The challenge is recognizing when to intervene and how to incorporate integrated pest management programs. It would be interesting to find a tipping point or a threshold in mongoose populations that can trigger management responses. However it might be difficult to find a threshold, largely due to the unknown fluctuation in population numbers. A long term monitoring program is necessary in order to evaluate if control programs are effective in the area. Having this information might save both time and cost. Understanding mongoose presence in a system like the tropical forest, and when to value new species assemblages, could provide new opportunities for biodiversity conservation. Recognizing that more than 100 years of presence in an area might be tied to a complex food web is important and has implications for population management strategies. A new approach can move managers to understand a system highly dominated by invasive species. I caution, however, that the discussion presented here might be unique to Puerto Rico and this approach needs to be carefully evaluated for other islands. Dr. Waltington brings forth an important issue with mongooses and rats that, as biologists, we might have overlooked. Novel animal communities provide opportunities for testing hypotheses or models on how introduced species at different trophic levels affect community structure, or what are the assembly mechanisms and community patterns. In conclusion: is this species naturalized already? I don't like labels, the mongoose is an important predator in the foodweb of the island and the reservoir of rabies, thus conservation managers will know how to manage mongoose population according to their priorities and funding available. We as ecologists are tasked with studying their functional role and importantly, communicating our findings! ReferencesKennedy, P. L., Lach, L., Lugo, A. E., & Hobbs, R. J. (2013). Fauna and Novel Ecosystems. In Novel Ecosystems (pp. 127–141). John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. doi:10.1002/9781118354186.ch14

Lugo, A. E., Carlo, T. A., & Wunderle, J. M. (2012). Natural mixing of species: novel plant-animal communities on Caribbean Islands. Animal Conservation, 15(3), 233–241. doi:10.1111/j.1469-1795.2012.00523.x Turvey, S. T. (2010). Evolution of non-homologous venom delivery systems in west indian insectivores? Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, 30(4), 1294–1299. Waltington-Linares, F. (2007). Presuntos implicados: Ratas y mangostas ¿plagas ecológicas? Acta Científica, 21, 53-60.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorEcóloga, Mujer y Puertorriqueña. Sarcástica, pero seria Archives

August 2022

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed