|

Although my work is not directly linked to community-based conservation and development, I have been involved in small projects as a volunteer back in Puerto Rico. I miss everything: the enthusiasm and desire to learn, the sense of community, new and strong friendships, and a common goal: protect our precious resources. As a grad student, however, I scan these projects with a critical eye. Why? Because I insists on taking Sociology and Political classes in Grad School which sucks the fun out of volunteering. It slaps my face and and open my eyes to see the bigger picture (Academia: where seeing the glass half empty is a +). Looking at literature I only found few examples of "successful" projects in developing countries. Here, I discuss what are the factors commonly associated to failure AND case studies in Zambia, Philippines and Costa Rica. Theories related to community empowerment, community power, social capital, traditional ecological knowledge and capacity building played a role in shaping community-based conservation projects. The general idea...Community-based conservation and development was proposed as a means to integrate environmental conservation and economic development in hopes to alleviate environmental problems in poor communities and also provide a source of income. McShane & Wells (2004) list some of the assumptions and objectives often provided in conservation and development programs:

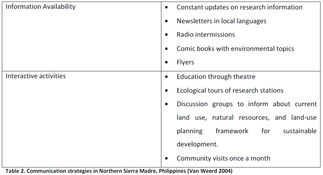

These assumptions have several, or too many, caveats. By increasing living standards in local communities, the pressure on biodiversity might increase by the higher demand for meat and other products. New development could influence in-migration and can further segregate marginalized groups. Not identifying the root cause for biodiversity loss in the areas, and assuming that local people and their land use is the sole cause of biodiversity loss, is a generalization that can affect the success of the project. There is also failure when a pre-conceived notion that the skills required to participate in a community-based management program are already in place. Theories at work...So what are SOME of the main ingredients for a 'successful' project? (*Note that the definition of success is relative here) I. Capacity Building - Current implementation is focused on tasks-results rather than adaptive learning for an adaptive management plan. By empowering communities via the process of governance, capacity building, and education over adaptive management, they are more prone to resilience over a radical change in politics and a bigger voice power over decision making. II. Power and Empowerment - A process of decentralization is necessary for participation from the local community to occur. Reaching a local consensus on resource use and investments via negotiation is a way for transferring control of projects from state to local community. A challenge for this is ensuring that the government will be responsive to the needs of groups. Waste (1986) and other scholars have indicated that a transfer of power should not to be given to individuals but to specific institutions. III.Capital - Creation of networks, collective action, set of rules in a community, trust, and reciprocity. "Greater social capital within a community can help in ensuring positive attitudes and better outcomes". Information and knowledge sharing among individuals in the community can be a method for enhancing trust.  Unfortunately, a significant number of these conservation projects have failed in the long term when implemented. Several factors are responsible for this: 1.) Lack of realistic and relevant goals 2.) Disinterest in decentralization of power and resources (no sense of social justice) 3.) Most of these programs are funded by international organizations. These organizations often try to apply a planned agenda which contains generic objectives and deadlines 4.) Time allotted to the development of conservation projects. By having strict deadlines, implementation takes place without a thorough study of the implications of the project for the environment and the community. Project in ZambiaThe project established in South Luangwa National Park was created in 1988 and adopted the name of Luangwa Integrated Resource Development Project (LIRDP). During the decade of the 1980’s the park adopted the concept of integrating the community as co-managers. The main source of income for the community surrounding the park was agriculture, which often provided low yields with little opportunity to benefit economically and thus putting pressure on wildlife for bush meat. The main goal: Providing an alternative livelihood through managing a safari hunting business and spreading knowledge about wildlife in order to decrease current threats. Main Actor: Power. Giving the community autonomy over certain areas of the park, property rights over land. Community was responsible for tasks such as law enforcement, maintenance of local institutions and some of the finances. Between the country’s government and the Norwegian government they developed and transition plan from dependence to self-sustainable form of profit, which was the conservation project through the safari and hunting business. Under this project 60% of all income went to management and maintenance of institutions and 40% went directly to the community (schools, housing, hospitals, etc).  Image credit: eyesonafrica.net Project in PhilippinesA surge in democracy in 1986 gave way for many democratic reforms that led to a reorganization of government initiatives The conservation approach taken by the Philippines was devolution of state power by implementing community-based projects nationwide. Called “Priority Protected Areas Project”, it sought to include representation of local communities and indigenous people. I very briefly discuss the project in Northern Sierra Madre Natural Park in the eastern coast of Luzon, which has a population of 23,000 people who live inside the park. The main source of income from around the buffer areas are timber harvesting, a land that was given to companies in 1965. The main goal: Reduce the intensity of floods and droughts in the area, which is a constant threat to the livelihoods of the residents. Protect the soil from erosion to help maintain the structure of the forest, and maintaining the integrity of the systems thus regulating local climate. Main actor: Outreach and participation. New protected areas can only be established after consulting and consent from the local community. Communication and public awareness were significant components of projects proposed for the park. From interactive sessions and focus groups, asking multi-stakeholders, and socioeconomic and biological data they came up with key issues that were affecting the community. Among these issues were: migration, limited livelihood sources, lack of technical knowledge and low level of environmental awareness.  Table from: D. Guzmán-Colón 2012. Working paper Main Actors: Local institutions. NGO’s were key for disseminating information and mobilizing community members to participate in the awareness-raising camping. Over the years, the students from a partnership between private and public Universities and the Dutch government funded socieconomical and biological research projects and have created a body of interdisciplinary knowledge on the subjects of forest exploitation, change over land-use, and forest policy.This partnership has been successful in setting up an information and training center on one of the campuses (Isabela State University). Project in Costa Rica Ostional Wildlife Refuge covers an 800 mile extend of beach and 200 miles of inland forest on the Pacific Ocean side of Costa Rica. Because of its history, it presents an interesting case of community-based conservation towards resource use. The refuge is known as the primary nesting site for the Olive Ridley sea turtle (Lepidochelys olivacea). Harvesting turtle eggs by the community in the area was the primary source of income and method of substance for the small population of the area, but in 1992 a road was built and it increased population in the area. The concern for overexploitation made the Costa Rican government deem harvesting illegal and created the wildlife refuge coupled with a research station. The local community was enraged, vandalizing research stations and still recurred to harvesting. Community members organized in subsequent years and decided to join scientists for finding an argument in favor of harvesting in the refuge. Scientific and social evidence was convincing enough that the government proceeded with a regulated harvesting program in the area. Main actor: Institutions and Secure economic benefit. The creation of institutions was of utmost importance in the development of this community-based conservation project. These institutions are all governmental, and have different responsibilities for the management of the project. The project was established with a solid legal, social and economic framework. Any decision made by the agencies has to have the approval of the community; community participation is insured by law. Unlike many other community-based conservation projects, the Ostional program had a steady source of income, which is the harvesting of turtle eggs for consumption or to sell. Harvesting is well regulated with groups going out each day and under the supervision of a biologist. Lessons learned.Although this was a brief and simple examination of the factors behind some of the projects that have been termed successful by scholars, there are some key events that stand out. In all three conservation projects, the devolution of land to the community and attempts of decentralization where the first steps towards the inclusion of the surrounding community. Some believe that a community is capable of managing their own projects but from these examples it is inferred that some sort of governmental institution is necessary for law enforcement and regulation. Another lesson learned from these projects was the importance of keeping the community informed via constant surveying and communicating progress.

Because of regional perceptions, different cultures and traditions, amount of ecological knowledge among other things that differ from place to place, it is best to assess the community first and ask what their needs are. Conservationists already know the needs of the ecosystem and wildlife, governments already know what their own needs are, now local communities, funding agencies, academics and governments need to draw upon interdisciplinary approaches and work in cooperation for improving what ‘community-based conservation’ is.

0 Comments

|

AuthorEcóloga, Mujer y Puertorriqueña. Sarcástica, pero seria Archives

August 2022

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed