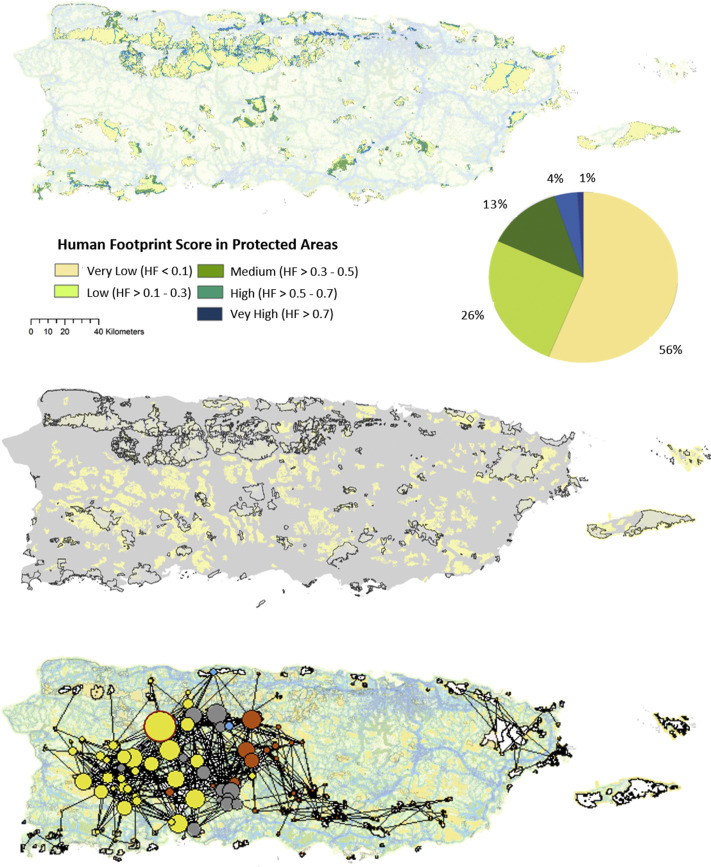

Islands make up some of the most important and imperiled biodiversity hotspots on Earth. In this study we re-scaled the Human Footprint for Puerto Rico and used network analysis to characterize the quality, area, and connectivity among natural landcover patches. (Link to publication) A global challenge for ecological conservation is balancing the sharing and sparing of land between anthropological and conservation uses. This issue is intensified in island ecosystems due to limited geographic area, isolation from continental resources, and high human population densities. Despite the growing extent of protected areas, extinction curves for islands generally remain steeper than in continental areas. A common strategy for conservation of species involves the protection of land. However, the location, size, quality, and connectivity of habitats are all important to consider when deciding which areas to protect. How can we incorporate all of these land attributes into models that capture both the function and structure of wildlife habitat, and that are scalable across global, regional, and local levels? I used Network Analysis, rooted in graph theory, to answer part of that question. I developed a map of the Human Footprint at a 30-m resolution for the island of Puerto Rico to identify areas that have a high index of naturalness. Using the Human Footprint as a cost-surface for potential species movement, I modelled spatially coherent networks of habitats linked by potential flows of organisms through the landscape matrix.  Figure: Protected areas in Puerto Rico and their Human Footprint Scores (Top). Low and Very Low human modified areas accounted for 82% (1, 129.96 km2 out of a total of 1, 378 km2). Medium to Very High modified areas covered 18% of protected areas (248 km2). Patches with a very low score and >25 ha (0.25 km2) outside of protected areas (center) are scattered though the central mountainous regions and almost non-existent in coastal areas. The Puerto Rico ecological areas network (bottom). Patch size represents number of connections and patch color represents the components to which each patch belongs. The patch with the most connections, the hub, was identified as part of the Karst region in the island (delineated in red). We found that Puerto Rico possesses a compact network of natural areas, with a few patches in the karst zone (west-center of PR) critical to structural connectivity. More than half of Puerto Rico’s current land surface had a low human footprint (56%), but coastal areas were highly affected by human use (82%). The main component of patches within the karst zone were of utmost importance for connecting isolated coastal patches to the main ecological network. Our analysis also suggests that Puerto Rico’s ecological network is likely to maintain its resilience in the face of frequent disturbances such as hurricanes. The high percent of natural landcover within our network is in large measure attributable to agricultural abandonment and subsequent second growth forest. Existing legal protections to the land in the western mountain region of Puerto Rico can be responsible for the tightly connected ecological network found. It is imperative to note that the protection of the rainforest and surrounding patches is critical for maintaining natural areas connectivity in the eastern region of the island. As urbanization continues to increase, identifying ecological networks of high conservation value on islands is a crucial step for land managers and policy makers. Connected ecological networks are critical in hotspots of biodiversity, and this is especially true for islands, which represent only 5% of global land area but contain a disproportionately high number of rare and endemic species. *My colleague Laura Farwell (SILVIS lab) also contributed to this story.

1 Comment

|

AuthorEcóloga, Mujer y Puertorriqueña. Sarcástica, pero seria Archives

August 2022

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed